Capitalism's Failure to Thrive

It's getting scary

Capitalism’s Failure to Thrive

By James Miller, January 2026

Where do we begin?

To begin, we must acknowledge that the capitalist mode of production is a system of social relations based on the production and circulation of commodities. As such, it is a product of historical development. It would be mistaken to assert that capitalism has been in existence for millions of years. Likewise, it would be a grievous error to imagine that capitalism will persist and thrive for millennia to come. If you believe either of these postulates, then I suggest you have stumbled upon the wrong essay.

I base my arguments on the historical reality of the birth and evolution of the capitalist mode of production in Europe, starting from the seventeenth century, and its subsequent expansion throughout the world. I take my point of departure from the Communist Manifesto, drafted by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1848, which summarizes the significance of the birth and spread of this system. And I develop my arguments further, basing myself on Marx’s explanation of the laws of capitalist in his 3-volume book, Capital, which explains why capitalism is a transitory mode of production that, in the final analysis, creates the forces that bring about its own destruction. We are now witnessing the waning of capital’s vitality and the increasing pace of its decay in the 21st century. This process has a strong tendency to provoke a widening gap between the lifestyles of the wealthiest capitalist families and those of the masses of workers, farmers, and small business operators. The open expression of the struggle between these classes will prove that Marx understood the nature of capitalism very well.

For Marxists, it is important to understand that the events we are witnessing today are a result of the progress of humanity from its earliest beginnings to the present day. Why would anyone want to say, “I know economics, but I don’t really know much about anthropology—these are two separate disciplines”? But let’s take a look at this “separate disciplines” principle. Can you truly say that economics and history are “separate disciplines”? Can you say that anatomy and physiology are separate fields? Or that biology and psychology are different sciences? For many of us, the problem is that we fall into accepting the mode of organization applied in setting up departments in the universities. This mode of organizing the curricula of higher education was determined by those who created and paid for the universities in the first place, and who have controlled their curricula and policies ever since. Were these people—for the most part very wealthy—really interested in producing a form of education that favored the education of the entire population?

If we look closely, we can recognize that there is a problem with this method of segregating disciplines. Students, in most cases, attend college to get a degree so they can become professionals and live well. They don’t go to school to learn the deepest truths about humanity—its origins, its biological evolution, its cultural evolution, and its perspectives for the future. If we want to understand the ideas that most effectively reveal these processes, we need to attend courses freed from the doctrines that were established by the exploiting classes to control the lower classes. For a deeper look into this topic, feel free to read my Substack essay: “The subordination of the social sciences to capital”:

—https://jmiller803.substack.com/p/the-subordination-of-the-social-sciences-996

Marx and Engels founded a partnership to examine and explain the history of human civilization so that masses of people could follow their example to study and learn about the world in order to be able to change it. Their life’s work was devoted to helping the working classes learn about how to make their way toward winning their battles against the wealthy rulers who held them in their oppressive grip. The more we learn from Marx and Engels, the better we can understand the problems we face and how to work together with our allies towards resolving them.

But of course, Marx and Engels wrote in the 19th century, and now we are dealing with problems that have been developing for almost two centuries since the Communist Manifesto was written. How does reading what Marx wrote back then help us understand what is happening today? We should point to the themes that Marx explained that are still relevant today. The first is value—value in exchange of products, value as a quantitative measure of one product in relation to another, and value as a store of purchasing power.

What is money? Why precious metals? What is fiat currency? Also, we should take a look at the circulation of money—what speeds it up or slows it down? Then there is credit—why is there so much borrowing nowadays? What is the significance of the federal debt? Why has it grown so high? And why have modern advanced nations magnified the quantity of outstanding debt to a far greater extent than ever before?

Marxism helps us to understand how these features developed throughout history, and how they can be recognized for what they are—a stage in the development of civilization. Marx and Engels understood that capitalism was a transitory stage of history, and further, that all stages of history were temporary. There are no historical periods that exhibit “eternal” existence. There are no galaxies or stars that have always existed and will exist forever. The universe, and everything in it, is temporary. Eternal life is not possible.

One more important aspect of the work of Marx and Engels is that they lived their lives as revolutionaries. Their work was not just to “impart knowledge,” but to create a working-class movement that would be capable of representing working-class interests in society in one country after another, and bring about a workers’ state, which they called the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” In this context, the term “dictatorship” meant exclusive rule, which indicates that the old ruling classes—the capitalists, bankers, and landlords—would be excluded from political power. This means that the significance of the growth of capitalism is that its advances in production capabilities creates the material basis for a higher stage of social development, one in which warfare and exploitation would be abolished and the whole purpose of production would be to promote the well-being and development of the potentials of human beings.

Value and Money

Marx’s “law of value,” or “labor theory of value,” was developed from his studies of the writings of previous economists, starting with William Petty (1623–1687). The main point of this theory is that the rate of exchange between two products of labor is a function of the quantity of human labor expended in their production. In the 18th and early 19th century this proposition was not controversial. U.S. politician, printer, scientist and philosopher Benjamin Franklin provided his own definition of the law of value. Here is a quote from his article, “The Nature and Necessity of a Paper-Currency,” (3 April 1729).

—https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-01-02-0041

Marx pointed out that the quantity of labor that served as the standard of value could not be explained by the time expended by each worker, or group of workers, on each particular product. Given the circumstances in most exchanges of products, the time it took for a worker to produce this or that particular product is not known, and it would be tedious, or impossible, to derive. Rather, it was the “socially necessary labor time” normally required at the given time and place. In the course of buying and selling between individuals or groups, standards of quantity developed spontaneously. The law of value goes back many centuries and asserts itself without anyone’s awareness—it first appears as barter, later as sale for money. Engels explained this principle in “Law of Value and Rate of Profit,” an essay included as an appendix to the third volume of Capital. Here, Engels explains that the law regarding rates of exchange between particular products of labor began in primitive communities that were bartering with one another. Engels wrote:

“But how, in this barter on the basis of quantity of labor, was the latter to be calculated, even if only indirectly and relatively, for products requiring longer labor, interrupted at irregular intervals, and uncertain in yield—e.g., grain or cattle? And among people, to boot, who could not calculate? Obviously, only by means of a lengthy process of zigzag approximation, often feeling the way here and there in the dark, and as is usual, learning only through mistakes. But each one’s necessity for covering his outlay on the whole always helped to return to the right direction; and the small number of kinds of articles in circulation, as well as the often century-long stable nature of their production, facilitated the attaining of this goal.”

—MECW, Vol. 37, p. 876

Without understanding value, how can we understand money? How do we know the difference between real money and fake money? Of course, we might have seen movies showing how experts identify the difference between real dollars and counterfeit. But we need to go deeper. History has shown us how important the introduction of money exchange was as a precursor to capitalism. It’s not just a question of what it looks like. And for this, we need to examine history to find out how money came to be. In the same essay, Engels wrote:

“From the practical point of view, money became the decisive measure of value, all the more as the commodities entering trade became more varied, the more they came from distant countries and the less, therefore, the labor time necessary for their production could be checked. . . . partly their own consciousness of the value-measuring property of labor had been fairly well dimmed by the habit of reckoning with money; in the popular mind money began to represent absolute value.”

—MECW, Vol. 37, p. 886

Marx showed that money was a way of representing labor value in the abstract. That means that those who possessed money could exchange for all products, provided that the value of the money was equivalent to the value of the product being purchased. He called money the “universal equivalent.” Over time, money became representative of the value, and medium of exchange for any other commodity because of its recognizability as pure exchange value—no matter what your need might be, you could use money to obtain it instead of bartering useful objects. But it had to be real money. The introduction of money became increasingly common among primitive communities as they evolved towards class-divided civilization. In his economics notebook known as Grundrisse, Marx explained how the growth of money as means of exchange and store of value, over time, developed into the formation of hoards of gold, silver, copper, or bonze in the hands of some individuals and families.

But going back to Marx’s analysis in Grundrisse, we read:

“To hoard money as such, the individual must sacrifice all relation to the objects that satisfy particular needs, he must abstain, in order to satisfy his need or greed for money as such. The greed for money or quest for enrichment is necessarily the downfall of the ancient communities. Hence the opposition to it. It itself is the community, and cannot tolerate any other standing above it. But this implies the full development of exchange value, hence of a social organisation corresponding to it.”

—MECW, Vol. 28, p. 155

Metallic forms of money—plates, pellets, bars, coins, etc.—whose weight had to be evaluated to determine their value, developed into representations of “wealth,” which emerged in ancient times in Mesopotamia (Babylonia) and Egypt more than 4,000 years ago. With money, certain individuals could hire armies and engage in military activity. That was the beginning of civilization. Today we still hear the expression: “money is the root of all evil.” Or, as we read it in the King James version of the book of Timothy, “For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil.”

And we can refer to the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, dating from about 4,000 years ago, which refers to gold as money. According to this legal system, there existed a relationship between gold, measured in a unit of weight called a “mina,” which could then be regarded as so many “shekels.”

For example, the English translation of this Code tells us:

“203. If a free-born man strike the body of another free-born man of equal rank, he shall pay one gold mina. Or this:

“204. If a freed man strike the body of another freed man, he shall pay ten shekels in money.”

Marx explains why gold came to be recognized and used as money in normal, everyday exchange of commodities. In Capital, Vol. I, Marx argues:

“In proportion as exchange bursts its local bonds, and the value of commodities more and more expands into an embodiment of human labour in the abstract, in the same proportion the character of money attaches itself to commodities that are by nature fitted to perform the social function of a universal equivalent. Those commodities are the precious metals.”

—MECW, Vol. 35, p. 99

We need to address the underlying problems

What defines a capitalist society is the fact that everyone in the population needs money to obtain the necessities of life. Workers receive money as wages, and the wealthy classes (bankers, landlords, and capitalists) receive money in the form of interest, rent, and profits. The middle-class occupations (teachers, lawyers, soldiers, entertainers, doctors, etc.) receive their money income in the form of fees, honoraria, taxes, etc. Marx counterposed “capitalist” society to “natural economy,” a form of social organization based on sharing the products of labor within a community, or bartering between communities. Barter develops when nearby communities exchange their products because each wants to obtain the products of the other. In the course of history, barter helps to create the local and regional markets for the emergence of money exchanges.

But the main reason to recognize that money is made of specific weights of precious metals is to recognize how abnormal it is that the U.S. dollar is not money at all. It is a form of credit. This has been true since 1971, when the U.S. government terminated the relationship of the dollar to gold. At that time, the U.S. had what it considered were valid reasons for abandoning the gold backing for the U.S. dollar.

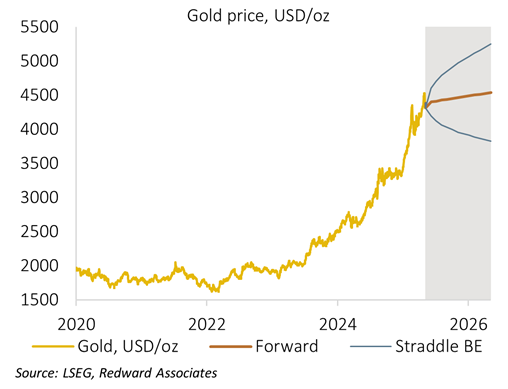

Now, in 2026, the world has seen the price of an ounce of gold rocket upwards well past $4,000/oz. It is the pressure of supply and demand that has pushed the price of gold up—but really, you should say that the inflationary pressure pushed the exchange value of the dollar down in relation to gold. Of course, this signifies the “devaluation” or “depreciation” of the U.S. dollar.

But then, we have already said that the dollar had no value to begin with, so how can it be devalued? It has lost its “nominal” valuation. The dollar, in order to act as valid payment for all debts public and private, had to treated, by all the entities relying on purchase and sale, as though it had real value. The significance of “nominal value” is that everyone regards fiat currencies as “real money” since they are accustomed to buying and selling with them on a daily basis.

But even though we recognize it is not real money, but that it works fine for purchasing—then what’s the problem? There are two problems. First is that dollars can be created out of thin air—and not just by the government. In everyday life, banks create money out of thin air when they issue loans to borrowers. Modern banks utilize the “fractional reserve banking system,” which allows banks to loan out funds in excess of the available reserve funds in their accounts.

Money loaned out to borrowers, for whatever purpose, adds to the total money in circulation, increasing the rate of inflation. When the quantity of money in circulation grows rapidly while the number of commodities entering into circulation grows more slowly—or even declines—we can see how this imbalance pushes up commodity prices. Price increases occur in commodities that circulate to satisfy the needs of the population, as well as the costs of production (the supply lines of manufacturers), and the selling prices of commercial and residential buildings. Further, inflation increases the funds available for investments (financial assets, such as stocks or bonds). In periods of high inflation, stock prices tend to rise rapidly, creating the illusion of an increase in wealth for the stockholders. A share of stock might double or triple in price, while there is no change in the underlying value of the company. These shares become mostly “fictitious capital”—(Marx’s term).

Thus, banking regulations have sought to limit the growth of the money supply through the fractional reserve banking system. We must keep in mind that, since there is no precious metal guarantee for the validity of the dollar (or pound, or yen, or euro) the potential to create money simply by adding numbers to a bank account is unlimited. The governing board of the Federal Reserve Banking system made this change in March 2020.

“As announced on March 15, 2020, the Board reduced reserve requirement ratios to zero percent effective March 26, 2020. This action eliminated reserve requirements for all depository institutions.

—https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/reservereq.htm

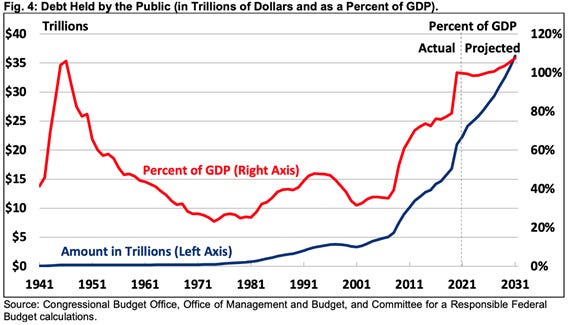

The U.S. bond market is for the buying and selling of Treasury bonds by whoever participates, including individual and family investors, businesses, or creditors belonging to any of the world’s nations. Apart from the banks, the U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve Banking System collaborate to sell U.S. Treasury bonds, bills, and notes to the public. These Treasuries make up the federal government debt, which in December 2025 stands at $38.4 trillion. But if we are going to fully understand the meaning of the national debt, it should be said that this money is not “owed” by the government to anyone. There is no need for “collateral.” The government has accepted money from bond buyers with no intention of “paying it back.” All bondholders recognize that if they wish to “cash in” a bond, they will need to find a buyer. Apart from this, there are periods of time when the Fed decides to build up its balance sheet, and will purchase bonds from bondholders and add them to its resources. This is an operation that is considered very helpful in boosting the borrow and spend propensity of the public, as was the case from 2008 to 2016—under the “zero bound interest rate” policy, which was termed “quantitative easing.”

When the Fed purchases Treasury bonds in the open market, it pays cash, and in this way increases the cash in circulation. Many dealers and banks buy and sell bonds regularly, seeking to increase their profits by paying less on their liabilities and receiving more for their assets.

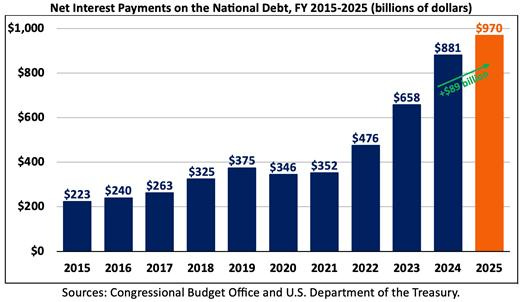

Collecting the interest payments was the motivation for these bond-buyers in purchasing the debt instruments. And we see then, as the total outstanding indebtedness increases, the amount paid to the bondholders rises accordingly. The total interest payments have been increasing exponentially, and in 2026 amounts to $970 billion—which is now the largest single expense in the federal budget.

In the early 20th century, money was made primarily by producing and selling products that helped to expand the economy. But in the late 20th century, production was increasingly offloaded to countries, while in the U.S., capital was shifted into the sphere of financial markets: stocks, bonds, futures, and derivatives. The total of all categories of growing indebtedness—state and local commercial and residential debts, household debts of all varieties, and obligations to international trading partners for the receipt of imports in exchange for U.S. forms of credit—add up to an accelerated course toward an economic crash.

Jack Barnes, central leader of the U.S. Socialist Workers Party, explained in 2008:

“Above all, the floodgates opened to a massive expansion of so-called derivatives, ‘securitized debts,’ ‘off-balance-sheet’ banking operations—in short, complex bets that the capitalist financial boom and mammoth acquisition of U.S. Treasury debt by the governments of China, Japan, and other countries would go onward and upward forever. Smaller and smaller amounts of collateral—sometimes little or no collateral—stood behind ever more leveraged loans, with less and less provision of any kind for the skyrocketing risk.”

—https://www.pathfinderpress.com/products/clintons-anti-working-class-record-why-washington-fears-working-people_by-jack-barnes-

After the wrenching international financial crash of 2008, the U.S. government followed a policy of “quantitative easing,” buying bonds to boost the balance sheet of the Fed and lowering the federal funds rate to near zero. This period was characterized by an increased pace of money-printing to artificially shore up purchasing power in the economy. The rapid rise of dollars in circulation created inflation of consumer goods as well as of stocks and other financial assets. The tendency to finance government expenses by selling Treasury bonds grew stronger—the government could have raised taxes, or cut discretionary fiscal spending (social security, Medicare, disability, etc.) but that would have created an outcry from all sectors of the population. Instead, they adopted a policy of funding government expenses by selling more bonds to investors of all nationalities. This rapidly raised the U.S. debt and forced the executive branch to request that Congress vote to raise the debt ceiling every year.

The Covid-provoked shutdowns of many businesses in 2020–21 lowered the output of the economy and increased the rate of unemployment, as well as the number of workers whose wage income was substantially reduced. The government then doubled-down on the money printing, sending out billions of dollars of compensatory payments to large masses of U.S. residents. The federal indebtedness mounted rapidly until 2022, when the government—recognizing the damage being done by high inflation—shifted to a policy raising interest rates to curb inflation. Higher interest rates tend to discourage borrowing to purchase houses or cars, etc.

The fact that the U.S. dollar has become the global reserve currency puts the U.S. in the position of being the world’s bully. The reserve status of this dollar has been, for the past 50 years, a method for accepting imports from other nations without paying for them. Instead of trading goods for goods—values for values—the U.S. gives tokens of credit in exchange for real goods. This is a boon for the avaricious U.S. capitalists, and the only reason they get away with it is because the U.S. dollar has become the obligatory currency for the pricing of goods in international trade, and the best means of settling the balances. The U.S. takes goods from China and gives the Chinese exporters U.S. Treasury bonds in return. This is getting the goods for free.

And the deeper reality has now emerged into the open, that no one wants to see the economy descend into recession. Every economy-watcher knows about the massive potential for bankruptcies of banks, insurance companies, pension funds, and major industrial and commercial enterprises in general. Millions of people would lose jobs, homes, assets, and possessions of all kinds. It is this deepening fear of collapse that is causing the breakdown of the two-party system and the growing vituperative exchanges we are witnessing within the political systems of the advanced capitalist countries. The billionaire ruling class is genuinely worried. It is as if they were in a car, speeding toward a cliff, and they suddenly realize that the brakes have failed completely.

It’s important to remember what Jack Barnes (see above) said about the impending catastrophe arising out of the rampant greed for money that motivates the capitalists in their quest for more, and more, and more . . .

“The underlying contradictions of world capitalism pushing toward depression and war did not begin on September 11, 2001. Some were accelerated by those events, but all have their roots in the downward turn in the curve of capitalist development a quarter century ago, followed by the interrelated weakening and then collapse of the Stalinist apparatuses in the Soviet Union and across Eastern and Central Europe at the opening of the 1990s. . . . One of capitalism’s infrequent long winters has begun. With the accompanying acceleration of imperialism’s drive toward war, it’s going to be a long, hot winter.”

—https://www.pathfinderpress.com/products/capitalisms-long-hot-winter-has-begun_by-jack-barnes

Signs of the impending catastrophe

Now we see growing interest in bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. This reflects a fear of the U.S. dollar, and other fiat currencies, which are falling in purchasing power and losing their capacity to store real value over the long haul. But the key problem is that investors are obliged to trust that the blockchain is always secure, that no one—no matter how clever—can hack cryptocurrency storage facilities. But we should be aware that cryptocurrencies are stored on computers, which need electricity to run. Those who trust these assets therefore depend on the safety and reliability of the electrical grids, as well as the security of the data centers themselves, and often the crypto investor doesn’t even know where these facilities are, or who is managing them. Naturally, crypto investors are provided with mountains of guarantees, authentications, certifications, etc. But this is just pro forma paperwork—they have nothing real to hold on to.

Gold is a physical substance, and when investors have gold in their possession, they will be able to sell at a later time, unless civilization breaks down. Discussions are underway among precious metals customers and storage providers about the safety of holding gold, and about the details involved in maintaining security. Are safe deposits in banks good enough? Is it advisable to acquire a safe to keep valuables at home? Are there precious metal repositories that can hold your gold in such a way that you are certain that your gold is safe? These discussions are important if you decide to purchase physical gold (bullion or coins).

In January 2026, we see that the gold price has shot up from less than $2,000/oz. in 2022 to over $4,400/oz. in January 2026.

But we need to recognize that the move toward ownership of gold involves not only individual investors, but institutional investors—banks, hedge funds, insurance companies, private equity funds, and the central banks of many nations. I think we can all recognize that the economic activities of all nations require a stable currency so that wage income has the expected effect of protecting workers’ standard of living. The more rapid the rate of inflation in consumer products, the more difficulties the workers experience as their wages purchase less and less. Not only do workers shift their voting preferences, but increasingly they recognize the need for a union that is strong enough to force wage raises. The frequency and effectiveness of strikes will increase.

But at the same time, if the public policy of the government keeps pushing prices up, all the institutions that strive to preserve and expand the wealth of the owners of capital experience this upward pressure on prices. If wage raises are granted, this increases the cost of keeping workers on the payroll. The prices of all inputs into the productive process—raw materials, semi-finished goods, equipment, tools, electricity, etc.—all push up the costs of production for manufacturers, as well as capitals invested in construction, transportation, mining, etc. And of course, as the purchasing power of the dollar falls, every sector of investment experiences the upward push of inflation. Stocks and bonds also become inflated.

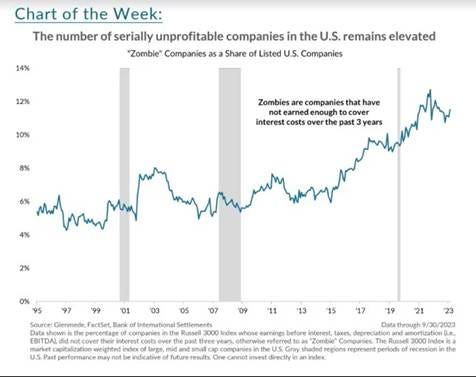

And it’s critical to understand that as long as the inflationary spiral is in effect, it feeds upon itself, producing ever higher debts. Thousands of businesses of all sizes are slipping towards the status of “zombie companies”—companies that consistently lose money year after year, and yet remain active, with properties and employees repeating the same tasks over and over.

Why do zombie companies persist? Many of these companies believe that if they retain their resources, employees and reputation, they can return to profitability. The banks continue to keep them alive by renewing their credit annually, because these companies show up as assets in their accounts. Meanwhile, the rate of bankruptcies has also increased in the early 21st century, and we know the names of the major retailers of yesteryear: Sears & Roebuck, J.C. Penney, Neiman Marcus and Brooks Brothers; auto companies Chrysler and GM, and entertainment companies like Blockbuster, Broadcom and Circuit City. Nor should we forget the crash of 2008, which wiped out Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch. Many commentators refer to these failures as “misallocated capital.” Of course, that’s true. But you could see a pattern of increasing exuberant high-risk stock investments starting with the Internet-related “dot-com” boom of 2000, and then leading into the fully catastrophic crash of 2008.

After this crash, the whole climate for business was scrutinized. The “too big to fail” policy of government bailouts for insolvent banks initially was denounced as a “free ride” for billion-dollar gamblers. But while the public was told that such shenanigans would be curtailed in the future, in reality, it wasn’t long before the same largesse for big business was started again, but under a different name: “quantitative easing.”

The Treasury department, working with the Federal Reserve system went into inflationary mode. Quantitative easing, implemented by the Fed, increased the Fed balance sheet by buying Treasury bonds already existing in the market, thus pushing down long-term interest rates. At the same time, the federal funds rate was lowered, making it easier for all banks to reduce interest rates and maximizing the conditions to borrow and spend. Due to this stimulus, indebtedness of all categories rose.

At the same time, the Treasury stopped tax increases and handed out more tax credits to keep up the level of borrowing and spending among the entire population. The administrations of Obama, Trump, Biden (and Trump2), together with the legislative branch of government, continued to sidestep the need for taxes to pay government expenses, and instead voted to raise the debt ceiling year after year. Meanwhile, the Treasury worked the money machine overtime, printing dollars, flooding the economy with spending power. These policies allowed the federal debt to rise to the current level—$38 trillion.

But don’t forget—these $38 trillion dollars are not just numbers in a spreadsheet. These are debts “owed” to real people—the government is required to pay them an agreed-upon amount of interest every year. As the total debt grows, the amount of the federal budget devoted to making these interest payments increases at an exponential rate.

The effects of the crisis have spread in all directions, leading to fear of recession, fear of losses of wealth, losses of jobs, stock market crashes in Europe, North America, Japan, etc. This is the situation. Many commentators and analysts can still believe in a recovery. The basic economic philosophy they advocate does not indicate the necessity of an end to capitalism. Whether they are Keynesians or Austrians, or in between, they see capitalism as an essentially permanent system. Only Marxists see it as temporary.

Productivity and Profit

A problem overlooked by all non-Marxist economic analysts is the falling rate of profit. Marx understood why—in the long run and in the final analysis—profit rates would fall. He didn’t think that this concept was particularly difficult to understand, but, however true that might be, no one but the Marxists—including Jack Barnes (see above)—write about it. And this falling rate is based the growth of the productivity of labor through the introduction of increasingly effective modern technology for manufacturing. As the tooling and machinery become more sophisticated, and as their design and usage become more automated and self-sufficient, human labor becomes less and less necessary to produce the optimum output.

One example of this is the transition from conventional precision machining in the manufacture of metal, plastic, or wooden components and parts to computerized numerical control machining to accomplish the same task. This eliminates the need for a human being to operate the controls that guide the cutting tools. There is a person who clamps the metallic piece into the machine, but then all the cutting runs automatically, following the coded instructions in the computer’s program. In this way, one operator can load and unload 10 or 20 machines in the time that used to require 10 or 20 operators, each one manually performing the cutting motions.

It’s not hard to see that for this transition the manufacturer must increase the investment of capital in machinery and tooling in all sectors of manufacturing, while the capital needed for wages of workers declines as a fraction of the total investment. And of course, similar gains in productivity occur in mining, infrastructure, and building construction, petroleum drilling, etc. To get a good appreciation for these productivity gains, I recommend Robert Bryce’s 2014 book Smaller Faster Lighter Denser Cheaper: How Innovation Keeps Proving the Catastrophists Wrong.

https://www.amazon.com/Smaller-Faster-Lighter-Denser-Cheaper/dp/1610392051

In any industrial or mining sector, the introduction of labor-saving machinery by one company induces other competing companies to follow suit and introduce the same, or similar, modernizing equipment. Thus, the whole system—all sectors—are affected by the same pressures of competition. Needless to say, there are plenty of mergers and acquisitions, leading to fewer competitors in each sector. Over time, the costs of production decline, since everything is produced quicker, and the tooling and machines themselves become cheaper. Robert Bryce’s book explains these tendencies.

But then comes the item that is not understood by economists trained to believe that capitalism is a natural and permanent system. The profit only derives from the human labor involved in the productive process. No profit comes from the machinery, tooling, purchased components, raw and auxiliary materials. Profit comes from human labor, and the less labor the company employs in proportion to the materials and equipment, the lower the profit rate, whether measured by the hour, the day or the year. The profit rate is the total profit divided by the total production expenditure. If a business increases its pace of production, or scale of operations, the mass of profits might rise while the rate of profit falls.

The capitalist pays an equivalent value for machines, tools, raw materials, components, auxiliary materials—everything that is bought from another capitalist. This leaves the only source of profit being the labor force employed. But why must the capitalist pay full price for the equipment? Because if the capitalist pays a lower price for a shovel, a cutting tool, or a barrel of lubricant, then the seller of that material is receiving a price that is lower than the actual value. This would mean that capitalists in the sectors manufacturing goods that are being sold to the producers of consumer goods are being cheated.

But capitalism cannot function if one group of capitalists systematically cheats another group. Each capitalist is free to invest in any sector, so that while one sector appears to be more profitable than other, capital is attracted to that sector. Thus, over time the capitalist’s profit rate tends to equalize across all sectors. This is not hard to understand. (Of course, in this context we are examining capitalism’s basic, normal functional processes. So for this purpose, we need to set aside external factors that can distort normal capitalist functioning, such as wars, criminality, taxes, etc.)

The reason why capitalism was so successful during the past three centuries lies in this simple truth—capitalists in each country profit more-or-less equally from the circumstances of free markets and the ability of each capitalist to easily move investments from one business to another. Once the capitalist magnates conquer state power, pre-capitalist autocracy and tyranny no longer interfere with the production and exchange of products. The capitalists themselves form the governments that suit their needs, and the aristocrats, nobles, and royalty of the previous historical period are removed from political power. Capitalist regimes prefer a democratic form of government—at least insofar as their own interests are concerned. Of course, these regimes offer different standards when it comes to the conditions of life faced by wage workers. That’s another question.

See my essay, “The Crisis of the Capitalist State”:

https://jmiller803.substack.com/p/the-crisis-of-the-capitalist-state

Now we see how productivity rises with the growth of the material elements of the productive process greatly outpacing the growth of the active labor power involved in the total value of the capital invested. From this we can recognize why—in the long run and in the final analysis—the rate of profit falls. This is because the rate of profit is a function of the labor value newly added in the production process, by the hour, by the day, by the year, etc. Every day so much labor is performed and the value added by this labor accounts not only for the wages paid to the worker but also for the profit appropriated by the employer.

But does the value of the materials also go into making up the profit? No. As we have said, and as Marx explained, the capitalist must pay an equivalent amount for the raw materials, machinery and auxiliary materials that are used up in the course of production. The profit only comes from value newly added by labor. Marx explained in Capital, Vol. III:

“A fall in the rate of profit and accelerated accumulation are different expressions of the same process only in so far as both reflect the development of the productive power. Accumulation, in turn, hastens the fall of the rate of profit, inasmuch as it implies concentration of labour on a large scale, and thus a higher composition of capital. On the other hand, a fall in the rate of profit again hastens the concentration of capital and its centralisation through expropriation of minor capitalists, the few direct producers who still have anything left to be expropriated. This accelerates accumulation with regard to mass, although the rate of accumulation falls with the rate of profit.”

—MECW, Vol. III, p. 240

But when we try to examine what Marx said, or what he and Engels were trying to accomplish, we should recognize that in the modern world, there are many self-proclaimed “Marxists” who have no revolutionary aspirations. These are professors, students and writers who learn Marxist terminology, themes, and categories, in order to be able to teach Marxism in universities and earn a decent living from this kind of work. Or sometimes they want to be seen as Marxists for political reasons, even though they have perverted Marxism beyond recognition. Many of these academic, or false, Marxists—while they might be capable of interpreting Marxism in some respects—misinterpret Marx’s ideas, and end up leading their students astray. Much more could be said about this. If you would like further development of this theme, please feel free to read my essay defending Marx’s explanation of the falling rate of profit against the misinterpretation of the theory provided by Paul Sweezy:

https://jmiller803.substack.com/p/why-the-profit-rate-must-fall

Apart from the Marxists and pseudo-Marxists, needless to say, the major media today provides plenty of space for conventional pro-capitalist commentators, all of whom stay away from Marxism. We know that many of these analysts are astute observers of the present crisis of capitalism, and we would be quite foolish indeed if we thought we had nothing to learn from them. Marx himself spent much of his life delving into the philosophy, research, and theorizing of the political economists who came before him, and who provided the material that allowed him to probe into the nature of capitalism and develop his theory. We end with Marx’s motto:

“Nothing human is alien to me.”

--https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1865/04/01.htm